I bootstrapped my first startup in high school and failed - This is what I learned

November 22 2023Ebenezer Zergabachew

Some of the best decisions I've made were completely spontaneous. No planning, no research, no well thought out analysis, just action. I've made some of my worst decisions the same way too but thats a post for another time.

In the 9th grade, I decided to sell candy just to see what would happen. The first day was a trial run. I had gum, mentos, and snickers. The mentos sold first, nobody bought the gum, and I was cleverly finessed off the snickers.

The next day I brought 3 mentos bars to school and sold them within 7 minutes of stepping on campus. I figured I had a winning product. I scaled that up and began moving thousands of calories of sugar through the student population.

Surprisingly, my saccharine solicitations were frowned upon and I was getting tired of getting called into the principals office. Though it wouldn't be the end of my Willy Wonka days (that too is a post for another time), this pushed to me to figure out what I could do off campus to make money without getting into trouble. I teamed up with my friends and began brainstorming ideas during lunch time. This lead to the birth of my first startup.

The Market

Growing up in Addis Ababa, I saw firsthand how the digital infrastructure that is ubiquitous in developed countries is under-utilized, suboptimal, or even non-existent in Ethiopia. One example of this is in financial technology, especially with consumers. Though now its beginning to be more well adopted, digital payments weren't a thing during my sophomore year of highschool. Given that Ethiopia was a cash economy, transactions were completed through cash or bank transfers.

Surprisingly however, e-commerce was a thing. Sort of.

Most people have mobile phones, and one of the most popular social media apps is Telegram. In addition to chatting with individuals, one of its most promising features is creating channels that people could join. This is a simple use case but it boasts great applications.

There are (even to this day) Telegram channels with well over 200,000+ users where people advertise products, services, job openings, and content. There are dozens of these mega-sized channels for people to trade items. If you wanted to post an ad on these channels, you would contact the admin, agree on a payment, and he would post the ad for you. Sellers would also have a Telegram channel that would act as a digital storefront for their businesses. Fashion boutiques, electronic stores, and various other small to medium sized businesses would use Telegram for marketing, lead generation, customer relationship management, order fulfillment, and various other functions.

The problem is that Telegram is not built for any of that shit. It's a social media app, not an e-commerce platform. This problem would manifest itself in very painful ways for both buyers and sellers...

The Problem

Having seen the potential in this space, my friends and I began customer discovery. We called hundreds of sellers we found on Telegram and asked them about their struggles, experiences, and pain points with the platform. We figured that if we asked enough people about their problems, we'd be able to figure out a solution.

One thing that these sellers kept bringing up is how customers flake on them. The buyer would see an item they like, they'd contact the seller and arrange for a time and place to complete the transaction, but when the time comes for them to actually buy the item, they'd ghost the seller.

This was obviously a painful problem.

It was also a problem that sellers experienced often. When asked how often they experience this, sellers responded that about 20% - 30% of their customers would flake!

Whats fascinating about this problem is that this data didn't exist until we started asking around. There wasn't a study that analyzed this problem. There isn't a central body of Telegram sellers that formally discuss their challenges with selling their products. These are owners of small businesses or guys that flip shoes on the side.

The fact that all these people kept saying the same numbers over and over again made me realize that this is a problem worth solving.

To combat this, some sellers would have their customers make a down payment first. But this is an inconvenience for the buyer. I experienced this myself when I wanted to buy a shirt but the seller told me to pay up 50%. I wasn't about to walk all the way to the bank, wait in line, and deposit money for an item I haven't received yet. Thats too much work on my part.

The problem of customers flaking ended up hurting the customer too. The user experience of buying these items was worsened because sellers can't trust a buyer unless their money is on the line. But I can't blame the sellers, it's perfectly reasonable to make a buyer jump through these hoops as insurance of their seriousness. The downside is that they'll lose potential customers as a result. I would have bought that shirt if it didn't cost me that much time and effort.

Its a solution to the problem of customers flaking.

But it is not an elegant solution...

Our Thesis

We identified a growing market with a painful and clearly quantifiable problem. Regardless of the context, 30% is a massive number. And in the context of money and time wasted, its egregious. If we can solve this problem, it would mean that we would make our clients 30% more money. That is a very clear value proposition for sellers.

After looking into the issue further, we hypothesized that it is ultimately a problem of friction. If there is no friction to buying an item (like simply messaging the seller) then a buyer is more likely to flake. What do they have to lose? But if theres too much friction (like a down payment), then it'll push away buyers.

If we could strike a balance with an optimal amount of friction in the buying process then it'll mean we can filter out non serious buyers without losing potential customers.

Now of course the perfect solution for this would be a platform that incorporates online payments, but that wasn't an option back then. There were very few digital payment solutions at that time. Some banks did have their own online payment gateways but they were really protective of their APIs. The rest had a poor user experience or no users at all.

Solving this problem meant figuring out a creative solution.

The Product

We didn't want to replace Telegram, instead we wanted to build a platform that would integrate with it seamlessly. It's obvious that no one is going to switch out of Telegram. Everyone uses it. The totality of our addressable market is on it. And the entirety of the sales cycle happens inside Telegram.

Building an alternative would have meant developing a product that is orders of magnitude better, on top of figuring out a distribution model to get everyone to switch platforms.

Instead, we decided to figure out how to build something within Telegram that automates the sales process. Whats great about Telegram is that it provides a lot of cool options for developers. You can build bots that users can interact with by viewing, posting, or editing data. The technical infrastructure for us to do what we wanted existed already.

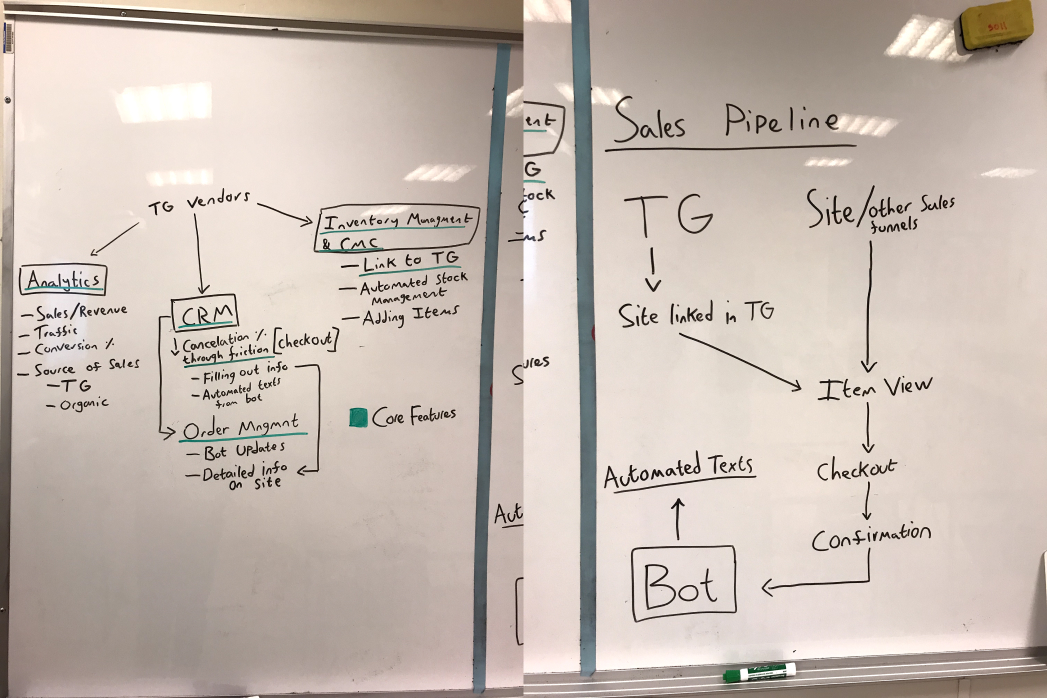

I remember having the epiphany of our product during class. It sounds corny but it really was one of those "flashing lightbulb" moments. I drew up wireframes and data flow diagrams of how our product would look and behave.

The idea was to develop Telegram bots that would interface between buyers and sellers.

A seller would get a link from the Seller Bot to post their items through a form on a webapp that would then store the info on a database. The bot will return a link to that item that they can share in their channels.

Buyers will tap the link in the channel which would take them to a form to fill out all the information needed to complete the transaction. After completing the form, they'll add the Buyer Bot to their Telegram account, which will provide an interface for them to view upcoming orders, contact the seller, or cancel an order early to avoid wasting the sellers time. Their bot will also send them reminders throughout the week. It was enough friction (or at least we assumed) that a buyer will fill out the form and use the bot if they actually wanted the item, but not too much friction to the point of abandoning the purchase completely.

This data will then be relayed to the seller through the Seller Bot, which essentially acts as a CRM for their digital business. Sellers will be able to manage all their customers, upcoming orders, on top of having an automated platform for tracking inventory and revenue.

After brainstorming names, we settled on Abay Shops. Abay means 'Nile' in Amharic, and it was a spinoff of another e-commerce company being named after a river. Our slogan would have been "The river that delivers." We envisioned Abay Shops being the digital hub of all consumer facing stores in Ethiopia, and eventually all of Africa.

It sounds good, at least on paper. But we wouldn't know until we built it. The only problem was that none of us could code. Which ended up being one of the driving factors that killed our startup.

How Abay Shops became ByeBye Shops

Being a 16 year old dumbass I kind of knew I was going to fail. Who was I to think I'd be a successful startup founder on my first try as a non-technical teenager with zero experience in the real world? But I wasn't scared of failure, I was however, really curious to see how far I could take this before it fails. There was a certain point I was going to reach before my lack of experience would fuck me over. I instinctively knew this. But I wanted to reach that point and see for myself.

At the time, we figured we could simply hire a developer to build it for us. So using the money I saved up from selling candy in school, we found devs (on Telegram) who told us they could build our product.

After a couple meetings, we signed a contract where we'd give a 60% down payment before they even started coding. That was a bad deal.

It wouldn't have been that bad if they had actually built the product, but delays, bugs, and the constant "we found a new framework" was killing our time and the trust of potential users who were willing to use Abay Shops. We no longer had any direct impact on Abay Shops, or at least it felt like we didn't. The only thing left to do was actually build it. And we kept waiting on the developers to finish the product. When the pandemic started, we lost all our momentum. We were sitting on our asses waiting for someone else to get our shit done.

Having delegated the responsibility of building the product to someone else, we were essentially left with nothing to do. And we began to lose motivation and passion to keep going. One year of lunch time meetings and a finite fructose fortune later, Abay Shops died.

A lot of it was my fault though. I can't put all the blame on the developers for the product not being built. What we assumed was an MVP was not an MVP. There were a host of features that weren't 'minimal' at all. Advanced analytics dashboard for sellers, storefronts on the web page, and a bunch of other unnecessary features that convoluted what was supposed to be a simple test to validate underlying assumptions.

Though the devs weren't disciplined or professional (they used a bunch of cuss words and slurs for dummy data when showing us a demo), I also contributed to the failure of Abay Shops by my failure to prioritize only what is important. I wonder how much money and time we could have saved if I was able (or willing) to cut down on features.

Looking back at it, I always cringe when I remember how much unnecessary bullshit I made the team go through just because I felt like it was the smart thing to do. Market research on spreadsheets (useful but not a priority), arguing about the cap table (a big point of contention and a massive distraction), and the worst one of all: writing an 8 page business plan (a useful exercise in pretending to be an entrepreneur but accomplished nothing of value in the process).

Given the distractions, complications, lack of focus, and poor decisions I made, it was obvious that Abay Shops was going to fail.

Lessons I Learned

Surprisingly, it didn't even bother me that much. Obviously I would have rather had it succeed, but deep down I knew it would fail. I surprised myself knowing how far I got and it gave me data that can inform me for my next venture. In retrospect, I'm glad I had that failure in highschool and not as an adult. I could afford to lose lunchtimes and candy money, but my risk tolerance will significantly lower the older I get. I learned so much in the process and I'm glad I went through all of it because the experiences I've gained are lessons I'll take with me for the rest of my life. I did some things right, but a lot of things wrong. I figured it would be wise to write down these lessons. I can look back on this post to reflect on what I learned, and I may even help someone else reading this. If you find value in this post, let me know.

Lesson 1: Trying to start a tech company with no technical skills is like trying to talk to girls with no game

Unless you're lucky and have someone else do it for you, its going to be very painful.

Going into Abay Shops, I assumed I was going to be "the business head of the company" but that is supreme foolishness. The business head of a technology company should know how that technology works. As "the business head of Abay Shops" I was signing stupid deals and getting finessed by my lack of technical knowledge ("the delay is because we discovered a new framework that will optimize your product for your users, its called 'VueJS'").

I never thought I was going to be a developer, I tried learning to code in my freshman year of highschool but it didn't really stick with me. It wasn't until Abay Shops failed that I had a reason to learn to code and to do it well. I had promised myself that I'm never going to let technical incompetence be the reason I fail again.

I began learning HTML/CSS the summer Abay Shops failed. I did end up building it myself using ReactJS and MongoDB and putting it in the hands of some users in my senior year of highschool but I stopped working on it after starting university. Even though it didn't go anywhere, knowing I built it gave me confidence that I can do it again for my next idea.

With that being said, its not impossible to start a tech company without knowing how to code (its been done before), but you should at least have a foundational understanding of how the technology works. Even if you have a technical cofounder, you don't want to be completely oblivious of your products technology during meetings. And chances are, even if you're not touching the code, you probably have an impact on it.

It's worth understanding how technology works in this day and age. You'll be shooting yourself in the leg if you don't. If you've been thinking of learning to code (God may be giving you a sign) and don't know where to start, I suggest Brad Traversy's crash courses on YouTube. His videos have been an excellent resource for me and I highly suggest you watch them. I'll likely make a post on how to learn to code and link it here. Feel free to message me if you have questions on learning to code, I'll gladly help.

Lesson 2: If it takes more than a month to build its not an MVP

If I could go back in time to Abay Shops, I'd cut half the features out of the product requirement document we gave to the developers. That wouldn't have stopped Abay Shops from failing, but it would have definitely saved time and money. But its only because I went through that experience that I understand this now.

Working at Virginia Tech's Apex Center, I deal with founders every day, and this is a problem that is remarkably common. Founders are scared that if their product isn't perfect then their startup will die. They'll go through hoops treating their startup like its a production grade application thats deployed at scale instead of building something simple that they can put in the hands of people quickly.

One example that comes to mind is a duo of founders who've been working on their startup for well over 6 months. They were developing a web app, a native mobile app, and even purchased hardware to build a custom server to self-host their data.

But they had no users.

I'd hold them accountable ("if the MVP is not deployed by next Friday I'm roundhouse kicking you in the ribs") but to very little avail. It wasn't until I started working with them and laid out a plan of the absolute core features that they finally deployed a product that they put into the hands of users. What they failed to do in 7 months they managed to do in under 7 days.

I didn't leave any room for deviations, changing plans, or extra features that they think their users would need. Those come after launch. Very often I see founders trying to solve problems that they might experience as they scale ("we need this server so we don't spend thousands on AWS"). Though this might sound like the right thing to do, its inherently flawed.

Why solve a problem that doesn't exist yet?

The purpose of a minimum viable product is not to scale. It's to validate assumptions you have about your users and their problems and to collect data on what to do next. Eventually (if you play your cards right), you'll get to the point of polishing a production scale product that thousands of people use.

Furthermore, on the point of MVPs, I'd make the argument that you don't need to code it out. Now of course this depends on the product but I'll bet for a majority of use cases that you can build an MVP with a spreadsheet or a Notion page. Not everything must be code from the beginning.

If the problem I wanted to solve is going from point A to point B, I'm not going to build a car with an engine, transmission, and suspension system.

I'm going to put wheels on a piece of wood and call it a skateboard.

Lesson 3: Learn to smell bullshit and stay far from it

I didn't realize this until recently but there's a lot of people who can't identify that which is meaningless, convulated, and impractical. There's a reason why management consultants make the sort of money that they do.

I'm only beginning to realize this flaw within myself as well. Thankfully I'm getting better at avoiding stupid shit but I really struggled with that during Abay Shops.

I'd get blinded by feeling like an entrepreneur and instead of actually being one. I was playing startup, pretending to know what I was doing when I was really doing all the wrong things.

Having experienced and seen this for myself, I see it amongst other people too. So much of what people think is 'smart' is really just complicated (or useless) for no reason. Some people use big words to sound smart, or they wear a suit to look competent, or they make Gantt charts, SWOT analyses, business plans, or over engineer a product to feel like they're being productive when in reality they're running in circles.

It's not that these things have no value. There is a time and a place for big words, suits, Gantt charts, business plans, and meticulous engineering. But the improper application of these things at the wrong time can be a colossal distraction.

And there's a huge difference between being smart and being wise. It helps to be intelligent but you must have wisdom to prioritize whats important. And wisdom beats intelligence.

Every single time.

Lesson 4: Don't be an asshole

In retrospect, I'm not proud of the way I treated my cofounders. I was putting a lot of pressure on my friends to operate at a high level and I crossed some lines in that process. Though it came out of a passion for what I was doing, I didn't communicate my frustrations effectively. And in trying to get my cofounders (who were also my friends) to push the needle, I ended up being aggressive, toxic, and disrespectful.

Horrible traits to have in a cofounder.

I'm surprised that they were putting up with my shit. I get embarrased when I look back on these moments. I wasn't actually solving any of the issues. I was pouring gasoline on the flame by making my friends lives more stressful.

This taught me an important lesson in being compassionate. That doesn't mean sacrificing assertiveness for someones feelings, but rather knowing how to handle conflict and hold people accountable while also being supportive.

It's about balancing mercy and severity, something we see Jesus doing flawlessly in the 8th chapter of the Gospel according to John. But that too is a post for another time.

Lesson 5: Be an asshole

I should have been harder on the developers than I was on my cofounders. It was a bad arrangement from the jump because paying 60% of the money when 0% of the work was done makes no sense. I don't know why I let myself get pressured into signing that deal quickly (another red flag - getting rushed to sign a contract).

I realized the value of having developers for a project like this, but I went into negotiating with no other options or backups. Chances are that we wouldn't have found other devs who were willing to work for the price we were offering, so we were desperate. But this too taught me a valuable lesson.

If you're not prepared to tell the other side to fuck off and go to hell, you probably shouldn't be negotiating in the first place.

I think thats a good heuristic to have on these things.

Final Remarks

I'd like to end this post by pointing out that I am not a successful entrepreneur, at least not yet. I believe great insights can come from experiencing two sides of any situation. In the context of startups, thats succeeding dominantly, and failing miserably.

Thankfully, I've already seen one side of that equation. I do have some experience, and I believe experiences are meant to be shared. But I haven't seen the full picture so take everything I say with a grain of salt. If you've felt like this post was valuable to you, let me know. I'm open to having conversations and I wish you the best in whatever stage of your life you're currently in.